I wake to sleep and take my waking slow. / I learn by going where I have to go —Theodore Roethke

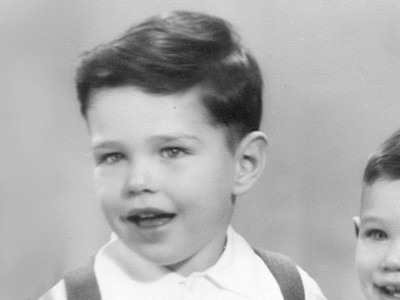

’m Trevor Goward and I begin with a question: Which of the four mug shots taken at different times in my life is the real me?

The answer is none of them. Indeed, the real me – and the real you, come to that – is not the person who’s eyes you peer into, rather it’s the person who lives behind those eyes and is always becoming.

In my case, probably the best way in is to consider the kinds of things I most attend to:

- Lichens for one.

- Canine friendship for another

- Game Trails for a third.

- The forests of home for a fourth.

- Deep-Snow Mountain Caribou for a fifth.

Let’s look at these.

My interest in lichens began as a form of apprenticeship to the Living World – the importance of knowing at least one kind of living thing very well – but gradually upgraded to Enlichenment.

Canine friendship began in simple companionship but later became: first, a form of communion with a species whose grandmother was our grandmother 300 million years ago; second, a form of extended meditation on the numberless ways of experiencing the Living World; and third, more recently, catalyst to the imperative for expanded pragmatics.

My interest in game trails began as a tracking exercise one winter of little snow, but later led: first, to long contemplation of the mind of the deer; second to Willder Trails; and third, through that, to a sense of their inherent power to lead us “home”.

The Forests of Home began as a desire to know my home place, but eventually transmogrified: first, to Island Earth; second, to a process of indigenization,; and third, through this, to a personal upgrade from environmentalist to Gaianist.

My advocacy for the Caribou who wander the mountains hereabouts began as an attempt to counter the gradual worldwide loss of wilderness, but eventually transformed to the insight that head learning is not enough, that we need to learn to care about the Living World itself.

You can check here for further biographic nuts and bolts, and here for a summary of my publications.

Next up: Valley Notebook