The scientific evidence is impossible to ignore: the forest is wired for wisdom, sentience, and healing —Suzanne Simard

Preamble When you enter an old forest, you enter a cathedral of life filled, in season, with bird song you can hear and, more than that, countless ecosystemic conversations you definitely cannot hear. The following unpublished essay was kindly prepared by Suzanne Simard appear in an upcoming book – Speak to the Wild – whose long-suffering manuscript expects to see the light of day in the not-too-distant future. As for Simard’s essay, it has lain dormant long enough …

Essay

ndigenous cultures have always known that forests are alive and filled with spirits – that a walk in the woods is much more than a walk among individual trees with nothing particular to say to one another.

Now there’s scientific evidence that basically confirms this, showing that trees and forest plants communicate and behave in ways that sustain the forest far beyond the lives of the individual. More than that, these findings awaken us to the possibility that trees and plants are sentient beings highly evolved at the community level.

The social community of a forest is in fact made up of scores of synergistic interactions among organisms of every stripe: herbs, shrubs, mosses, liverworts, fungi, slime moulds, bacteria, invertebrates, birds, mammals. And of course trees.

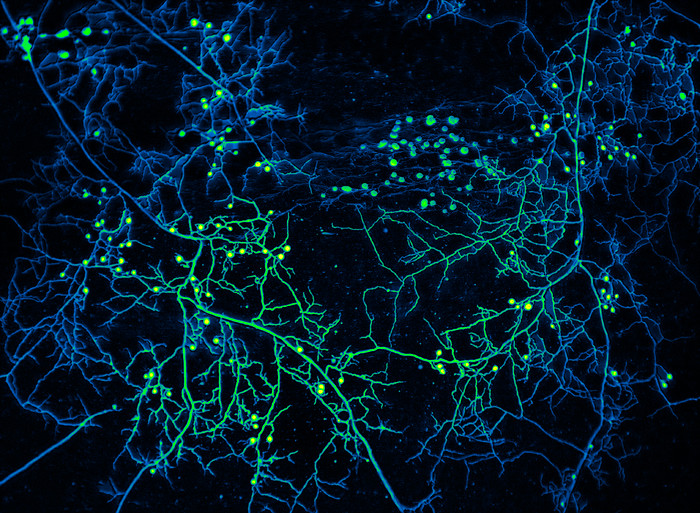

One such synergy arises in mycorrhizas, literally “fungus-roots.” Mycorrhizas are physical linkages between the roots of plants and trees – especially conifers – with the threadlike underground parts of mushrooms. While thousands of different species of plants and fungi form mycorrhizae worldwide, the phenomenon is most prevalent in places where nutrients are limiting to growth.

At one level, mycorrhizas are exchanges of convenience in which the host plant provides the fungus with photosynthetic carbon, while the fungus provides the host plant with soil nutrients and water. Critically, however, all mycorrhizal fungi have the capacity to link the roots of plants of the same or different species to one another. The mycorrhizae of Douglas-fir seedlings, for example, enable the young trees to tap into and withdraw nutrients from older trees nearby. This helps them acquire the resources they need for successful establishment.

In a sense, mycorrhizas resemble modern-day transportation or telecommunications networks. These networks form a ‘scale-free’ pattern in which large old trees act as hubs and younger trees as satellite nodes. Running through the ground, they enable nutrients and biochemical signals to move rapidly back and forth among members of the forest – a communication process apparently essential for the self-organization of the forest ecosystem.

Because mycorrhizal networks transport water, carbon, macronutrients and other resources along nutrient gradients from high concentration to low, they provide critical nutrient and chemical ‘top-ups’ for plants in need. Resource-rich paper birch trees, for example, have been shown to shuttle carbon to stressed Douglas-fir neighbours. Such carbon transfers appear to be causally associated with improved survival, growth and health of the recipient trees.

Established and regenerating trees that are linked in a mycorrhizal network can evidently recognize other trees of the same species. We have found that the older ‘mother trees’ can distinguish their kin from stranger seedlings, shuttling more microelements and supporting vaster mycorrhizal networks to close relatives, thus providing a competitive edge for kin seedlings. However, mother trees also share small amounts of resources with strangers – evidence that mycorrhizas benefit not just the members of a particular species, but the forest community as a whole.

This ‘mycorrhizal advantage’ extends also to trees injured by defoliation or pathogens. Such trees can use mycorrhizas to send out signals to neighbouring trees, which respond by increasing their defence enzymes. What’s more, sudden injury to a mother tree can trigger a rapid transfer of photosynthates to the healthy neighbour. Such biochemical exchanges – another form of interplant communication that again benefits the forest ecosystem as a whole.

The study of plant communication and behaviour is still a fledgling science, but what we know already is nothing short of revolutionary. Not only is it now clear that plants communicate with each other to promote the stability of the greater community, we are also finally coming to understand that the forest is, as the saying goes, much more than the sum of its trees. This new scientific understanding resonates with Indigenous teachings and is suggestive of sentience in forest ecosystems. It calls upon us to respect and learn from the ways of the forest.

May the forest be with you always —Trevor

Next up: Kincentricity