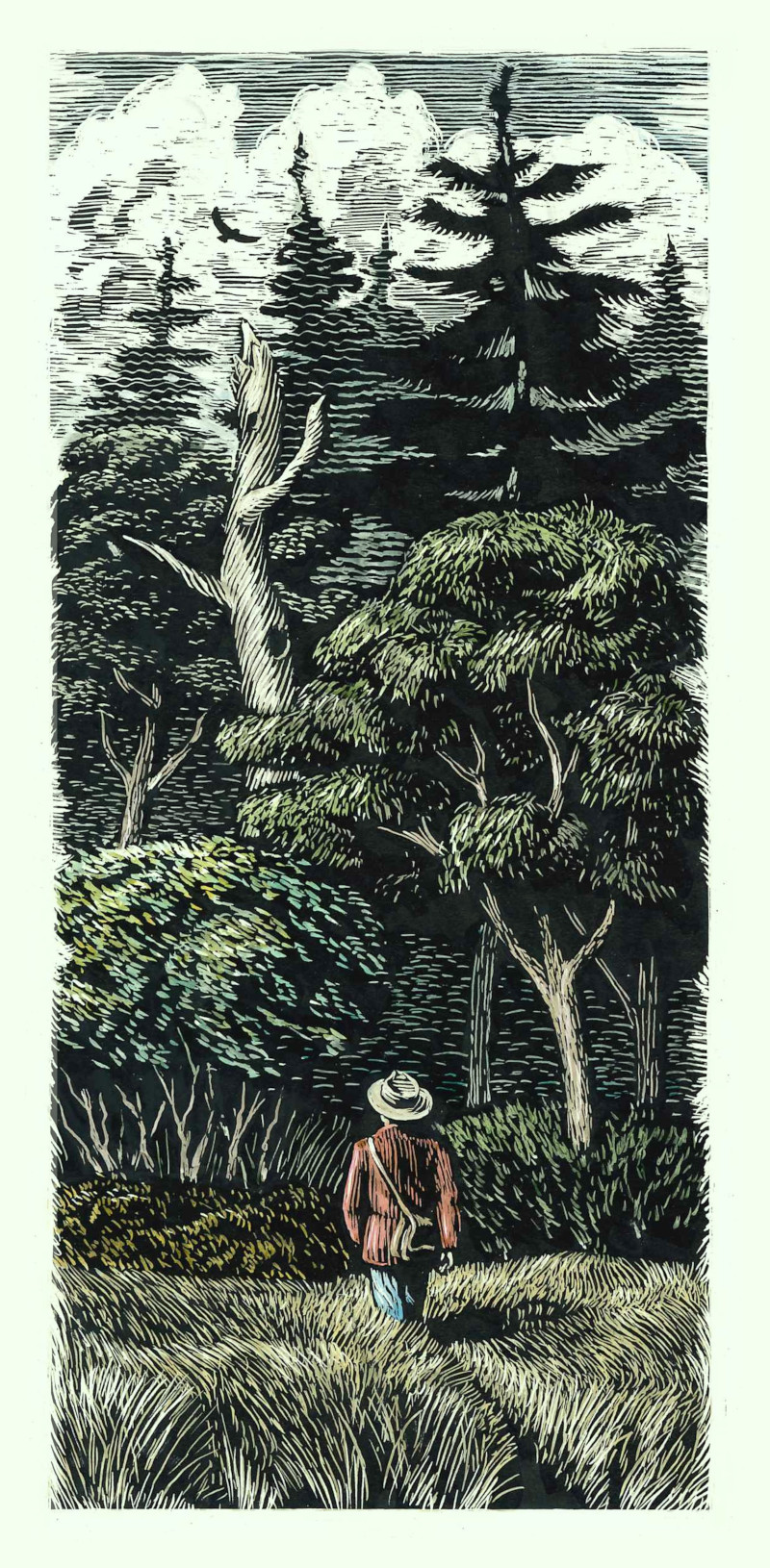

It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see —Henry David Thoreau

Preamble Edgewood Wild is structured around the insight that any path to a livable future for the greatest number must include, at a minimum, some sort of meaningful reconciliation with the Living World That Sustains Us.

What such reconciliation would or could or should look like, I leave to others to ponder. The only point I feel compelled to champion is this: that born naturalists — people endowed with high naturalistic intelligence — must sooner or later play a role, indeed a signal role in any future reconfiguring of the western mind toward this end.

First Approximation

n his 2000 book, Intelligence Reframed, Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner suggests that human intellectual capacity is helpfully understood as a variable amalgam of at least eight different aptitudes or styles of intelligence, which he terms bodily-kinesthetic, verbal-linguistic, musical-rhythmic, visual-spatial, logical-mathematical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalistic.

Now as a rule, gifted children, certainly in western cultures, are actively encouraged to develop their talents to full potential. It’s a no-brainer, really. If you’re born with high bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, let’s say, then very likely you’ll win all manner of accolades in school sports and maybe later find your way to a much-cheered career in athletics. Similarly, if you’re born with high musical-rhythmic aptitude, you’ll certainly be encouraged to join the school band and from there go on to who knows where.

But if you’re born with high naturalistic intelligence – born, that is to say, with a deep and abiding interest in and responsiveness to the Living World – then good luck; in our western culture, at least, nobody’s quite sure what to make of you. Invariably you’ll condemned to twelve formative years spent in indoor classroom settings where your gifts neither flourish nor are even generally recognized.

Have you ever come across E.O. Wilson’s metaphor about the full quiver? Few have. I can’t find the source, but I recall he was writing about tribal societies and their existential need for a full complement of human aptitudes – “arrows,” as he called them.

Thus, a tribe that in time of strife lacked, let’s say, willing warriors or a skilled leader to lead them, such a tribe would be unlikely to prevail against an opposing tribe in full possession of both.

Nor, for that matter, would a tribe in time of environmental duress likely endure if it didn’t pump out, at regular intervals, place-based knowledge finders/keepers – people with an inborn hunger for learning what they can about their surrounds – in other words born naturalists.

This way of thinking about naturalistic intelligence – as indeed about all the other intelligences recognized by Howard Gardner – points to a key role in the evolution of overall tribal intelligence. To state this more clearly, tribes endowed with a full quiver of human aptitude, including high naturalist intelligence, were (and are) more likely to pass on their genes than tribes that lack one or more of them.

So who then are these born naturalists, and what are their field marks?

By temperament, born naturalists are people endowed from a young age with seemingly boundless enthusiasm for roaming about in the out of doors and fashioning it into what might be called dream material. As a rule, they are captivated by the living things they encounter day-to-day – plants, insects, birds, mammals, etc. – are often feel compelled, starting at a young age, to collect and categorize, arranging their collections each according to kind.

As born naturalists approach early adulthood, they often distinguish themselves from their peers by a seeming curious indifference to the pursuit of gainful employment or social standing. Instead, they tend to dedicate an inordinate amount of time and energy to their particular naturalist interests – the salient point being that born naturalists, if given a choice, will generally engage obsessively with the Living World in preference to other pursuits.

Herein, I suggest, dwells a germ of hope. For we live at a time when ongoing societal disregard for the Living World translates to ever-increasing ecosystemic reconfiguration trending to chaos. At such a time, born naturalists arguably provide a crucial sustainable and, if encouraged, sustaining link to the more than human world. Born naturalists as Gaian lifelines.

I close with the thought that we would to well, in these Pandoracenean times, to bring all inborn human aptitudes to bear. The time is ripe to fully integrate born naturalists into western culture by making space for two societal functions they are eminently suited to serve, i.e., the Neighbourhood Naturalist and the Pandoracene Pathfinder .

Springboard to both of these functions is, I suggest, an opportunity for gainful employment as park naturalists – a vocation that would enable people born with high naturalistic intelligence to hone their talents while at the same time helping to effect a necessary science-based sea-change in our collective understanding of our relation to the Living World That Sustains Us.

Next up: Four Paths